After performing musicals such as Once Upon a Mattress and tales of romance such as Romeo and Juliet, Kentwood’s fall drama production explores the triumph of human perseverance in “The Miracle Worker,” which premiered Nov. 17.

“It’s going to be an incredible show,” Kentwood Drama Director Rebecca Lloyd said. “These actors are brilliant. They are brilliant in this role. They’re really, really good.”

The play, written by William Gibson, tells the story of Helen Keller who suffered from both blindness and deafness at a young age. Through a life-long relationship with teacher and friend, Annie Sullivan, she was able to overcome her debilitations and become a prolific writer and political activist.

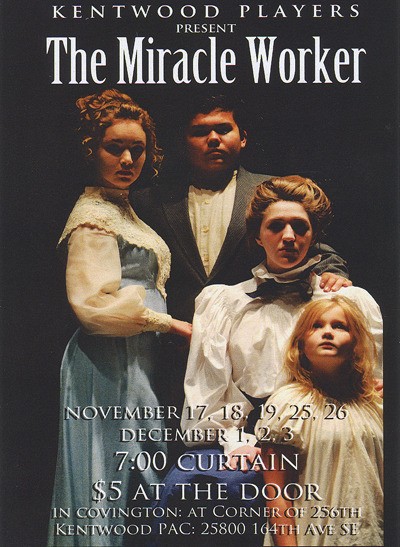

The role of Annie Sullivan, Keller’s teacher, is played by Kentwood junior Maggie Mosbarger while Sunshine Elementary fifth grader Megan Lewin plays a young Helen Keller.

Lloyd decided on this particular production because she felt Mosbarger had the background suitable for the part of Sullivan.

“I look at my kids and decide what play,” she said. “I picked this play last year for Maggie Mosbarger because I knew she would be incredible in this part. The way she is able to perform on stage — she’s just really intuitive and very sensitive to people who have to live outside of the mainstream.”

Other roles include Keller’s mother, Kate, played by Megan Ingales, her brother, James, played by KJ Knies and her father, played by Jordan Kawachi.

Knies also played Prince Dauntless in Once Upon a Mattress and Romeo in Romeo and Juliet.

Whereas Romeo and Juliet focused around young love, the theme of the Miracle Worker is tough love, according to Lloyd.

“She (Anne) believes in tough love before tough love was invented,” Lloyd said.

The story begins with Keller’s birth in 1880. At 19 months she contracted a serious illness which leaves her both blind and deaf.

Unable to see or hear, Keller grows up in her own world of darkness and isolation, a world which is never challenged by her family.

“Her parents coddled her,” Lloyd explained. “She does whatever she wants and she gets away with it. She feels entitled to do whatever she wants.”

Having exhausted their efforts to reach out to her, Keller’s parents bring in 20-year-old Annie Sullivan. Impaired with poor eyesight due to an infection, Sullivan was educated at a school for the blind, and while she empathizes with Keller’s condition, she is shocked by the freedom her family has given her.

“She (Keller) just goes from plate to plate and takes food (at dinner),” Lloyd explained. “Annie is appalled by that. She knows how things are supposed to be. She is appalled by how they have let this child dominate the house.”

Taking Keller under her wing, Sullivan attempts to teach Keller the meaning of words. The stark difference between her methods compared to that of Keller’s parents leads to conflict in several scenes which emphasize the chasm Sullivan must cross to get to Keller.

“Helen is not a sweet little girl,” Lloyd said. “She slaps people. She hasn’t been taught any better, so she doesn’t know any better, so it isn’t her fault but it’s still happening. Annie comes in and says ‘No I don’t think so.’ It’s a hard lesson for Helen, but, Helen finally gets it.”

Sullivan’s patience with Keller, as well as her unwillingness to give up on her, is one of the main focuses of the play.

“It’s Annie’s determination,” Lloyd said. “She believed the only way to get through to Helen is to make her understand what she needs to do. Make her see what she needs to do, because Helen became blind when she was about a year old, and she can’t see and can’t hear. So she doesn’t have any words for whatever is in her head, and she needs words for those things really badly.”

The play ends as Keller is beginning to learn the meaning of words and, Lloyd added, Keller discovers her own humanity in the process.

“Learning to be human, learning to be a thinking, feel human being,” she said. “If you’re just running over people, like the entitled do, then you’re not being a human being. You’re being a bully and that’s what she’s doing. She’s bullying the entire house.”

The play also highlights the complex reality someone with a handicap has to face.

“Being both blind and deaf is really a hard thing,” Lloyd said. “And so Annie’s struggle is to just recognize that one word makes it into her head and then all the other words will follow. She teaches her how to sign, and she thinks it’s just an activity at first, but then she just connects.”

Producing a play about a blind and deaf child proved to be tricky for both Lloyd and Lewin, as it required them to think of every action through the mind of a severely handicapped child.

“We take it for granted that we can see and talk and communicate,” Lloyd said. “What would happen if that was taken away from us? What if we couldn’t talk? What if we couldn’t hear? One of the things I have to do is Lewin is…has to move through the set — I have to put myself in that space as a blind child. When she starts moving across the stage without her hands in front of her — she’s supposed to be from one place to another — I’m like ‘Helen would never get there that easily.’ It’s been a real interesting lesson for Lewin and I and the rest of the cast. I think it’s a great Thanksgiving show.”

There will be performances at 7 p.m. tonight, as well Dec. 1, 2 and 3. Tickets are $5 at the door.

Talk to us

Please share your story tips by emailing editor@kentreporter.com.

To share your opinion for publication, submit a letter through our website https://www.kentreporter.com/submit-letter/. Include your name, address and daytime phone number. (We’ll only publish your name and hometown.) Please keep letters to 300 words or less.