Survivor shares memories of loss, liberation

Even at the age of 80, Mercer Island resident Henry Friedman still has vivid memories of his childhood in Brody, Poland — memories he wishes he could forget.

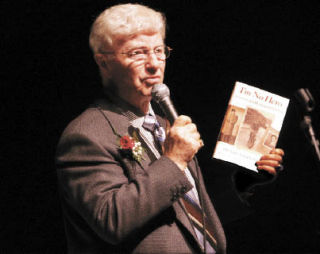

The Holocaust survivor related his haunting story to an audience of area students May 30 at the Kent-Meridian High School Performing Arts Center, giving the younger generation a firsthand account of one of the darkest periods in history.

Friedman, chairman of the Washington State Holocaust Education Resource Center, brought students back to 1939 Poland, when the Russians bombed his hometown and paved the way for Nazi occupation in the largely Jewish town.

“My city of Brody was burning, but what caught my eyes was a horse lying across from my house,” Friedman said. “He had such big eyes, and he had a big wound in his side — a bullet wound or a shrapnel wound. I was just mesmerized by the sight until my mother came over and put her hand over my eyes. I was 11 years old at that time.”

The Nazis invaded in 1941 and quickly began revoking many of the Jews’ basic human rights. Friedman lost three uncles to Nazi executioners within the first several months of occupation, and German officers raided his home, taking all of his family’s possessions. Friedman remembers trying to keep an officer from stealing his mother’s wedding ring from her finger.

“I ran looking for the pistol my father kept, and luckily I didn’t find it because I wouldn’t be here to tell you the story,” he told the high-school audience.

Every Jew was required to wear an arm band with the five-point Star of David for identification, Friedman said, and the new “law of the land” offered his people no protection from German and Ukrainian mistreatment, violence and murder. His mother was beaten so badly she couldn’t lift her arms for months, and his cousin was forced to clean out an outhouse with her bare hands, he remembers.

When Jews were herded into ghettos in 1942, the Friedman family went into hiding in a nearby village with two different Ukrainian Christian families. Friedman, his mother, his younger brother and a female teacher his father hired were hidden in a tiny loft in a barn, in which they only had space to sit or lay down. His father hid alone in a similar space in a nearby barn.

The family would be in hiding for 18 months.

Friedman had a white sheet the size of his old hiding place on stage at the Kent-Meridian presentation, and he invited four volunteers up to show the way they were situated in their hiding place.

“I was stuck there with two females and my kid brother, so I was not a happy camper,” he told the students. “Eighteen months I spent like that.”

He said the Christian family would send up two meals a day at first, but as the months wore on, meals were reduced to once a day. The four were freezing from the cold and slowly starving, but they had another problem. Friedman’s mother was pregnant.

He choked up as he told the students of the family’s decision to kill the baby to spare its suffering and ensure their survival. They took a vote, and Friedman admits his vote was to kill his newborn sibling — a girl.

“By that time we were infested with lice and fleas,” he said. “We were starving. We were living in constant fear. I sat facing the other way as my teacher helped my mother give birth to this miracle, and then she was killed. I tell you this so you understand how inhumane those times were.”

He said he still lives with the guilt of his vote.

“I’m 80 years old now, and I have to go to the grave with this guilt that when I was 14 years old I made a decision to kill another human being,” Friedman said.

In 1944, he said the family heard shells flying outside the barn walls, and it was “music to their ears.” The Russians soon liberated them that March, their bodies emaciated but still alive, and they returned to Brody in July to find the once 15,000-strong community of Jews reduced to less than 100. Friedman’s family was the only Jewish family in the town to survive intact.

Friedman’s poignant story was part of a long-running, annual Holocaust speaker series organized by Kent Mountain View Academy educator Pat Gallagher. This year’s series also featured Nazi death camp survivor Robbie Waisman and Buchenwald liberator Leo Hymas.

Gallagher said the series is aimed at educating young people about the atrocities of the past in order to better prepare them for the future.

“I think this is the only way to curb this type of thing happening again,” Gallagher said.

He also said World War II survivors are nearing the ends of their lives now, and there may not be many more chances to hear their stories.

“Liberators are dying at a rate of 1,000 a day right now,” Gallagher said. “These students will walk out the door in June having experienced something most students never will.”

Contact Daniel Mooney at 253-437-6012 or dmooney@reporternewspapers.com.

Learn more

To learn more about the Holocaust, visit the Washington State Holocaust Education Resource Center Web site, www.wsherc.org. Henry Friedman’s book, “I’m No Hero: Journeys of a Holocaust Survivor,” can be purchased online from major bookstores.

Talk to us

Please share your story tips by emailing editor@kentreporter.com.

To share your opinion for publication, submit a letter through our website https://www.kentreporter.com/submit-letter/. Include your name, address and daytime phone number. (We’ll only publish your name and hometown.) Please keep letters to 300 words or less.